10 years after the release of EURON Roboethics Roadmap, the world has been faced a critical technology revolution. We continuously witnessed Google’s self-driving car, Amazon’s KIVA system, drones, SoftBank’s Pepper, Boston Dynamics’ Atlas, ROSS System, and AlphaGO coming into our lives. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no more a science fiction concept, but the next wave to change our society. More interestingly, the intersection of AI & law will not only affect how people think, but also what people do in their daily life, how they behave. For this interview, we would like to invite Ms. Mady Delvaux-Stehres to share her insights on the European perspective on Robot Law.

Interviewee: Ms. Mady Delvaux-Stehres, Member of the European Parliament, Vice-Chair of the Committee on Legal Affairs, Chair of the Working Group on robotics

Interviewer: Dr. Yueh-Hsuan Weng, the Co-founder of Peking University’s ROBOLAW.ASIA Initiative, a founding member of The AI & Law Research Committee, China Law Association on Science and Technology (CLAST), Beijing, China and Tech and Law Fellow

Date: July 13th 2016

WENG:Thank you for agreeing to an interview. Can you tell us a little about yourself and your background?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:I am not a scientist, but I am fascinated by new technologies and their implications for our daily life. In fact, I studied classical literature (Latin, Greek and French) and I was a teacher until 1989, when I moved to politics. I held several ministerial roles (Social Security, Transport, Telecommunication and Education) before joining the European Parliament in 2014.

WENG:You are Rapporteur of the “DRAFT REPORT with Recommendations to the Commission on Civil Law Rules on Robotics”. This report has recently received great attention from international communities. Can you briefly introduce the report to us? Does it aim for creating a legal framework to support human-robot co-existence? When will its final version to be released?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:The report aims at providing guidelines and recommendations to the European Commission on a legal framework for robotics. It covers a wide range of different areas, such as liability rules, ethical questions, standardisation and safety, data protection, human enhancement or education and employment.

Until October, the other committees of the European Parliament concerned with the issue (Committee on Employment and Social Affairs; Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety; Committee on Industry, Research and Energy; Committee on Transport and Tourism) have time to give their opinion on the report. The vote in the Committee on Legal Affairs is scheduled for end of October and the vote in plenary is foreseen for January 2017.

WENG:There is another report called “D 6.2 - Guidelines on Regulating Robotics” (2014), which is the final output of European FP7 Project: ROBOLAW. Is it and your draft report both recommended guidelines for the European Parliament?What is the difference between them?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:The Robolaw research project was funded by the European Commission. It aimed at providing the European Commission with guidelines and suggestions for the regulation of robotic technologies.

In fact, the outcome of this project laid the corner stone of our work in the European Parliament.

I learned about the Robolaw project in a workshop in autumn 2014. Their results were very inspiring and it would have been a shame not to react to their great efforts and work.

With the own-initiative report,the European Parliament aims at expressing its own position regarding the creation of a legal framework on robotics and AI by providing guidelines and recommendations to the European Commission.

WENG: Does its title “recommendations to the Commission on Civil Law Rules on Robotics” mean that the resolution establishes general and ethical principles regarding the development of AI and robotics for civil use by private law? However, even if their applications only for civil use, regulators may still need to consider public laws as well. For example, FAA’s regulations for commercial drones, and UNECE’s motor vehicle regulations are beyond civil law domain. How do you see public law’s role in regulating AI and robotics for civil use?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:We exclude the military use of robots (robots as weapons) from the report and only focus on the civil use of robots. This is the reason of the report’s title.

Regarding the regulation of robotics and AI, both private and public law are playing a key role. For instance driverless cars: the Vienna Convention on road traffic is not compatible with any form of higher automation. Car manufacturers are developing cars that are able to drive autonomously but first the laws need to change to allow testing these new types of vehicle on public roads. Besides, we need clarification of all the liability questions arising with the development of automated vehicles, like the well-known question of “Who is liable in case of an accident?”

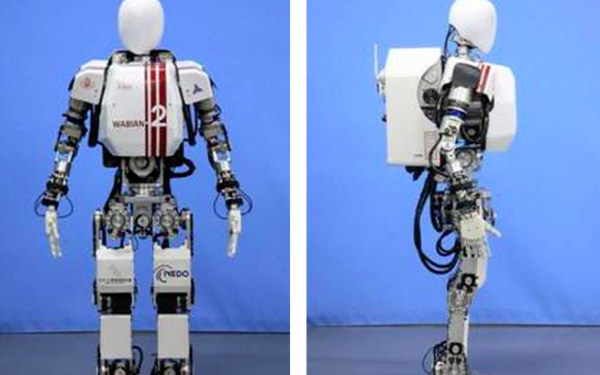

WENG:I have been conducting an empirical case study on legal impacts to humanoid robots with researchers at the Humanoid Robotics Institute, Waseda University in Tokyo. In order to reduce conflicts between advanced robots and existing laws, Japanese government has approved to establish the world’s first RT special zone in Fukuoka in 2003.The history of RT special zone is only 13 years long, but there are already many special zones established in Fukuoka, Osaka, Gifu, Kanagawa and Tsukuba. Also, many potential legal problems can be discovered in advance via the “Deregulation” inside RT special zones. Do you think that it is feasible to establish some deregulation RT special zones in Europe?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:In my opinion, testing robots in real life scenarios is essential for the identification and assessment of the risks they might entail, as well as of their technological development beyond a pure experimental laboratory phase. We definitely need to know more about Human-Robot-Co-Existence. This is why we call on the European Commission to draw up uniform criteria across all Member States, which individual Member States should use to identify areas where testing robots is permitted in real-life conditions.

WENG:Can you tell us why there is a need to create a new category or legal status for intelligent robots? What’s the major difficulty to realize it under current EU legal system?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:In future, more and more robots are able to make smart autonomous decisions or interact with third parties independently. A crucial question arises from this trend: Should the owner still be liable for damage caused by his smart robot? The creation of an e-personality for robots, at least for those robots with a higher degree in artificial intelligence and with self-learning capabilities, could be a possible way forward. However, in a first step, it is important to regulate more imminent current problems related to robotics like self-driving cars or drones. The e-personality for robots could be an option later, in a second step.

WENG:I am interested in your proposal for establishing an EU Agency for Robotics and Artificial Intelligence. Can you tell us more about this concept?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:The Agency should be staffed with engineers and specialists in robotics, but also with lawyers and philosophers in order to reflect on all the questions related to AI and robotics. A European Agency for Robotics has the potential to provide guiding principles to the European Commission and European Member States. Moreover, it could be the European interlocutor on the international level, especially with regard to the cooperation in establishing international standards.

WENG:Why is it necessary to draft laws that regulate the artificial intelligence and the robotics?

DELVAUX-STEHRES:The current legislation is not fit to cope with the emergence of smart autonomous robots and artificial intelligence. For instance, testing autonomous vehicles on public roads is not compatible with the Vienna Convention on road traffic. If we don´t act promptly, there is a risk that the economic potential and positive effects of robotics will not be fully realised in Europe. Besides the economic aspect, we need a clear framework to ensure the protection of the right to privacy, the data protection and to safeguard the security of European citizens.