|

October, 2013

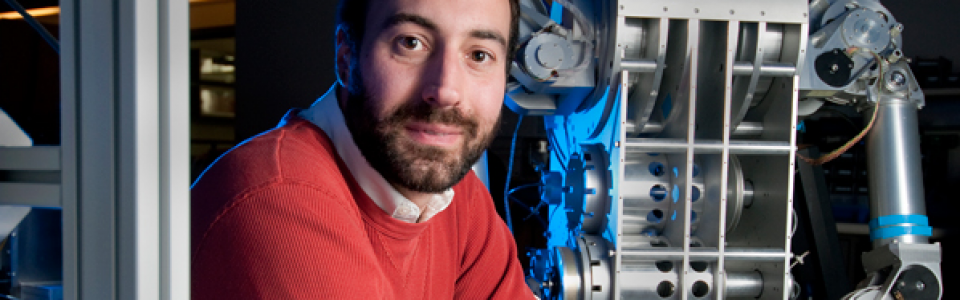

Tech and Law Center interviews Ryan Calo, Assistant Professor at the University of Washington School of Law and formerly a director at the Stanford Law School Center for Internet and Society (CIS). Ryan researches the intersection of law and emerging technology, with an emphasis on robotics and the Internet. He is the director of the Tech Policy Lab.

Paper: SSRN

Twitter

Do drones have the potential to be significantly more invasive than traditional surveillance technologies such as manned aircraft or low-powered cameras?

Yes. Drones drive down the costs of surveillance and, with lower costs, comes a higher likelihood that surveillance will occur. I was on NPR Talk of the Nation last year and a caller identified himself as a building inspector. He said he would inspect buildings more often if he had a drone because he would be able see violations without having to get access to the premises. That is just one example; we should expect many more as drones become more powerful and even less expensive

Drones are still largely associated with military strikes: which are the main other potential uses?

A lot the drone in the United States are actually used by hobbyists. But the main anticipated uses in the near term are in law enforcement and, interestingly enough, agriculture. Farmers want to be able to use drones to monitor and protect crops from pests. A third place we should expect drone use is in reporting the news.

Is privacy law keeping up with surveillance technology and specifically with drones?

No. Drones are actually revealing just how poorly privacy law is keeping up with advances in surveillance technology.

Are there other scaring technologies you might see upcoming?

I think drones are part of a broader trend toward cheaper, more mobile sensors. I also think about the ability of “big data” to sort through visual and other databases in search of criminal activity. I’m not afraid of any particularly machine, but rather am concerned about advances in certain technology that make abuses more feasible and hence likely.

What kind of liability could be applied to a drone if it causes inadvertently an injury to a physical person?

I think that no liability should attach to the manufacturer unless it resulted from their negligence. Rather, the operator of the drone should be held responsible—and perhaps have the opportunity to purchase insurance if he or she intends to use the drone in a risky way.

What will be the impact of drones in the United States in the next year?

Do you think it’s right to limit the use of drones only to law enforcement? The impact of drones will be limited because, until September 2014, the FAA continues to ban the private use of drones for commercial purposes. Once that ban is lifted, I believe the impact of drones on the U.S. will be profound.

The United States v. Jones ruling could limit how drones might be used for surveillance?

Technically none, since the decision was based on the officers’ trespassing on the car to attach the GPS device and drones need not be attached. But in Jones, five justices worried aloud that at least “electronic” surveillance was getting too easy, and might eventually violate the citizen’s reasonable expectation of privacy. I think it is too soon to apply this concern to drones, but could imagine one day, when drones can stay up in the air, autonomous and silent for a long time, that courts would invoke Jones in relation to drone surveillance.

|